When to Stop Driving

How can you tell when the time has come for someone to stop driving? Caring.com has developed guidelines that will help you avoid being an alarmist yet also realize when the time has arrived that driving is no longer a safe activity for the person in your care.

With one in six drivers in the U.S. today over 65 years old and an aging Baby Boomer population, there are more older drivers than ever on the road today. Understandably, the question of whether people should continue to drive well into old age is a contentious one. On the one hand, driving can help older adults stay mobile, independent, and connected to their loved ones and their communities.

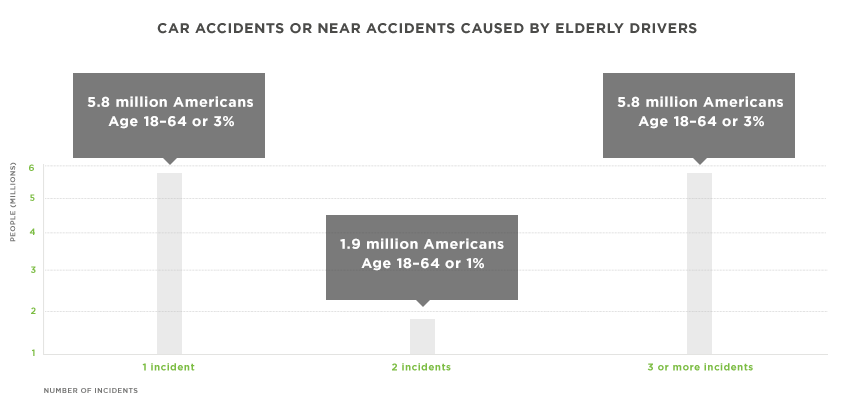

Yet, data consistently shows that driving gets riskier with age. Our 2015 Senior Driving study estimated that about 14 million Americans had been involved in a car crash caused by an elderly driver in the previous year. And the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention report that some 712 older adult drivers are injured and 19 are killed in auto accidents in the U.S. each day.

While old age alone is not a reason to stop driving, age-related physical and cognitive challenges such as slower reflexes or vision troubles can make driving difficult — even dangerous — especially past age 80 or beyond.

Recognizing the signs that an aging loved one is no longer able to drive safely is crucial. The next step is typically the hardest, though: how to talk to that loved one about giving up the keys. Where you might clearly see the danger of allowing an unsafe driver to continue getting behind the wheel, your elder loved one may fear the loss of their independence, ability to socialize and be a part of their community.

As you and your family tackle this difficult topic, we’ve collected a range of resources to help you understand and navigate the next steps.

Causes of Driving Difficulties with Age

It’s normal and inevitable to experience some age-related symptoms that make driving tougher as the years pass. Older drivers may be dealing with vision or hearing problems, not to mention reflexes that aren’t as sharp as they once were. In addition, many older adults in the U.S. suffer from serious, chronic illnesses that can impede their ability to drive safely, such as heart disease, diabetes, arthritis, Parkinson’s disease or dementia.

In fact, according to the CDC, drivers over 65 are twice as likely as younger drivers to report having a medical problem that makes it difficult to travel. And the risk of being involved in a deadly car crash starts to increase among drivers who are 70 or older, with the highest risk among drivers who are 85 or older, the CDC reports.

More worrisome still, drivers 80 and older have higher crash death rates than any other group except teenage drivers, according to CDC data. (One reason: Older drivers are physically more frail than other drivers and thus more likely to die in a crash.)

Below are some of the most common risk factors that can interfere with an older adult’s ability to safely operate a car. Having any of the following factors does not mean an older adult should immediately stop driving, but they can elevate risk and warrant monitoring.

1. Health Conditions

Physical and mental impairments that accompany aging, from Parkinson’s disease to dementia, can compromise driving agility and judgment. If you have questions about someone’s ability to drive given his health problems, consult with his physicians, if possible, and raise the issue of driving safety. (Keep in mind that his physician can’t talk to you without his permission, unless you have power of attorney.)

2. Vision Impairment

Vision is obviously a key component of driving ability. In fact, according to Elizabeth Dugan, author of The Driving Dilemma, “90 percent of the information needed to drive safely relates to the ability to see clearly.” From accurately reading the speedometer to detecting pedestrians on the side of the road, good driving requires good eyesight. But deterioration in vision is an inevitable effect of aging; in people 75 and older, vision impairment rates increase significantly, according to the CDC.

As the eye ages, far less light reaches the retina, for one thing. Older eyes are also more susceptible to cataracts, glaucoma, and other problems that impair vision. Encourage your family member to have regular eye exams, and check in with his eye doctor if you have concerns.

3. Hearing Impairment

Few people age without some deterioration in their hearing. In fact, one-third of those over 65 have hearing problems. Hearing loss can happen gradually, without the person realizing it, and undermine the ability to hear horns, screeching tires, sirens, and other sounds that would normally put someone on high alert. Make sure the person in your care has regular hearing tests.

4. Prescription Drug Use and Drug Interactions

Many drugs can compromise driving ability by causing drowsiness, blurred vision, confusion, tremors, or other side effects. Certain drugs taken in combination can also interact and cause serious problems. If your loved one takes a lot of pills each day, as many elderly people do, be sure to educate yourself about the drugs and their possible side effects. Even herbal remedies and over-the-counter medications can affect driving ability. Talk to your family member’s doctors and pharmacist, and be sure to ask about possible drug interactions.

Warning Signs of an Unsafe Elderly Driver

How can you tell when the time has come for someone to stop driving? It isn’t always immediately obvious when an elderly person begins to have trouble behind the wheel. Your parent or other aging loved one may not notice that her driving skills are deteriorating or may not want to acknowledge it — and you may not care to either.

Of course you want your parent to maintain her independence as long as possible, but don’t wait for an accident to happen before you intervene. We’ve developed guidelines that will help you avoid being an alarmist yet also realize when the time has arrived that driving is no longer a safe activity for the person in your care.

Watch for the following signs of a dangerous driver.

1. Car Insurance Changes or Traffic Tickets

If you’ve observed some questionable driving on your aging loved one’s part, ask whether they’ve gotten any tickets for speeding or other violations. Naturally, it’s best to do this in a neutral, non-accusatory way at a time when they’re not behind the wheel.

If you’re not comfortable asking about tickets, ask whether your loved one’s car insurance rate has gone up. If the answer is yes, this may be a sign that they’ve had recent driving infractions.

This is an especially telling sign for a driver that typically has not had tickets or warnings from law enforcement in the past.

2. Damage to the Car

When your aging loved one is not with you, walk around their car look for signs of damage. Everyone’s car gets nicked now and then by someone else’s door in a parking lot, but does her car have the kind of scratches or dents that could indicate driving mishaps? If so, ask her about them.

3. Reluctance to Drive

Notice whether your parent is reluctant to drive, seems tense or exhausted after driving or complains of getting lost. She may, for example, decline invitations to social events that require her to drive, particularly at night. This may be her way of acknowledging that she’s aware of her own limitations and is taking steps to avoid an accident.

4. Friends’ Observations

Discreetly check in with your loved one’s friends and neighbors and ask if they’ve noticed any driving problems. Don’t wait for your parent’s friends or neighbors to call you if you’re worried about your parent’s driving. They may feel uncomfortable approaching you with any concerns but may talk with you if you contact them directly.

If you live far from your parents, try to identify one or two such people who would be willing to keep you informed about your parent’s driving and other safety matters. Contact them regularly, and make sure they have your contact information too, so they can reach you if anything comes up.

5. Driving Behavior Changes

Take several drives with your aging loved one at the wheel, and observe their driving with an open mind.

Are they tense? Do they lean forward in their seat and appear worried or preoccupied? Does he or she often express irritation at other drivers? Do they seem particularly tired after driving? If so, your loved one is probably beginning to have some anxiety about driving.

When you accompany your loved one on an errand or an outing, encourage them to take the wheel and look for these signs of driving problems:

- Do they fasten their seat belt?

- Do they sit comfortably at the wheel, or do they crane forward or show signs of discomfort?

- Do they seem tense and preoccupied, or easily distracted?

- Are they aware of traffic lights, road signs, pedestrians and the reactions of other motorists?

- Do they often tailgate or drift toward the oncoming lane or into other lanes?

- Do they react slowly or with confusion in unexpected situations?

- Do they consistently wait too long to respond to traffic lights or other driving cues?

- Do they tailgate?

- Do they stay in their own lane or let the car drift very close to the centerline?

- Does he or she complain of getting lost more than she used to?

If you drive with him a few times and notice problems, it’s time to initiate a discussion about your concerns and whether it might be time for him to stop driving.

Professional Assessments of Driving Safety

If you’re not sure whether or not an older driver is safe behind the wheel, there are experts who can help.

The Driver’s Doctors

Make sure the driver is up to date with medical and vision exams. If you have concerns that health or vision problems may be impeding his driving abilities, tell his physician or eye doctor. Be specific about any symptoms you’ve observed.

By law, doctors can’t share medical information without a patient’s permission, unless you have medical power of attorney or your loved one has signed a HIPAA release. Even if he refuses to allow the doctor to give you information, you should still alert the physician if you’ve noticed symptoms or behaviors that worry you.

Driver Rehabilitation Specialists

A certified driver rehabilitation specialist (CDRS) is an expert — usually a driving instructor or occupational therapist — who is trained to evaluate someone’s driving abilities. A CDRS won’t hesitate to recommend driving cessation if she believes a driver is no longer safe. At the same time, she won’t tell an older person to stop driving if it’s not warranted, no matter what the caregiver wishes.

If an older driver is still safe behind the wheel but her skills could use improvement, a few sessions with a CDRS can help her break bad habits and learn new skills. A CDRS can also recommend safety devices, such as special mirrors or adaptive foot pedals.

If the CDRS concludes that an older adult is no longer safe to drive, she’ll help ease the transition by providing concrete information and support. Many driving programs and geriatric centers have such experts on staff. You can also find a CDRS near you by consulting the directory on the Association for Driving Rehabilitation Specialists’ website.

How the DMV can help ensure an older adult drives safely

First, do the research

If you’re worried about whether an older adult is driving safely, using your state DMV (Department of Motor Vehicles) resources may help. Many state DMVs now have websites that offer information and resources on older adults and driving issues, including driver-improvement programs and driver self-assessments. For example, California’s Department of Motor Vehicles even has a “senior ombudsman” who’s available to assist older adults and their families.

Our state-by-state driving calculator provides contact details for your state DMV, along with other useful information regarding older adults and driving.

When all else fails

If the person in your care flatly refuses to stop driving and you believe he or she poses a significant safety risk, you can file an unsafe driver report with your state DMV. A DMV representative will then contact your loved one and request a medical evaluation; a driving test may also be required. Depending on the findings, their license may be restricted or revoked altogether.

Some states conceal the identity of the person who makes the report; others do not. Even if yours doesn’t, your loved one’s potential anger at you for “interfering” is preferable to letting them injure — or kill — themselves or a pedestrian through a driving error.

Please click a state for information.

How to Have “The Talk” About Giving Up The Keys

If you have concerns about an elderly adult’s ability to drive, addressing them promptly could be a matter of life and death. It may be tempting to procrastinate — to talk to him next week or before the first snowfall, for example — but think how you’d feel if the delay led to an automobile accident that resulted in a serious injury or death.

Considering the possible consequences should help you overcome your hesitation — but that doesn’t mean it will be easy. It’s awkward and painful to have to inform older adults that they aren’t capable of doing something as basic and essential as driving the car. For them, it’s another humiliating reminder of their growing inability to take care of themselves and manage the tasks of daily life.

As difficult as it is, if you have reason to believe that the person in your care could be dangerous behind the wheel, it’s important to deal with the issue sooner rather than later — because later could be too late.

Plan Ahead

It’s a good idea to plan how you’re going to approach the subject before bringing it up. Take time to consider how the situation looks from the driver’s point of view and what driving means to him.

In his book How to Say It to Seniors, geriatric expert David Solie points out that because elderly people face so many losses at this stage of life, they tend to rigidly control the few things they can. This struggle for control will almost certainly come into play where driving is concerned, because giving up the car keys could affect where they live, who they see, and what interests and activities they can pursue. To you, this decision is a simple matter of good sense and safety; for them, it represents the end of life as they’ve always known it.

Make sure your expectations are realistic. If you assume that one discussion will neatly resolve the matter, you’re bound to be disappointed. Given how charged the driving issue is, you need to think of this as a process that will take some adjustment and fine-tuning. Consider this a preliminary discussion only; a way to get the issue out on the table so it can be dealt with openly.

Consider your own role. Remember that it’s not up to you to convince the person your caring for to immediately cease driving, even if you think this is the best course of action. Unless the driver has dementia or is otherwise incapacitated (see below), it’s best to respect his right to make decisions about his life — with your input and support.

Consider temporarily giving up the car yourself. Elizabeth Dugan, a geriatric researcher who wrote the book The Driving Dilemma, reports that a colleague stopped using his car for two weeks before talking to his elderly father about driving safety. His car-less weeks gave him firsthand experience of the inconvenience and lack of mobility that his father was going to have to endure. You may not want to give up your car before you talk with an older adult, but you should give some thought to the emotional and practical issues he’ll face when he gives up driving.

Plan your discussion for a quiet time of day. Find a time when you and the driver you’re concerned about are both relaxed and rested and no one has any deadlines or commitments pending.

How to Bring It Up

When you introduce the subject, try to avoid coming on too strong, or you’ll set the discussion off on the wrong foot. You may feel a keen sense of urgency, but if you jump right in with, “You have to stop driving! You’re going to kill someone!” he’ll probably either get angry or tune you out.

Remember that if you’ve noticed that his driving has grown erratic and sloppy, he’s probably aware of it, too. You can be most helpful by helping him express and work through his own concerns. A good way to do this is to initiate the discussion with a question. For instance, if you know that he has received a traffic ticket, ask him about it, and then follow up with another question like, “How are you doing with your driving? Are you finding it a little difficult to manage?”

Handle Objections With Reflective Listening

Your loved one may respond by pointing out all the practical reasons he can’t stop driving (“What about my weekly golf game?” or “My wife’s physical therapy appointments are clear across town!”). Without directly answering your question about his driving ability, he’s already making the case for why he can’t stop. This is valuable information because it provides a glimpse of his own internal struggle: He knows that he’s having trouble driving safely but can’t fathom how he’ll manage without a car.

Encourage him to discuss his concerns without immediately jumping in with solutions (don’t rush in with “I’m sure Jack or Stan will be happy to drive you to the golf course” or “The bus goes right by the physical therapy office”). It’s also usually counterproductive to offer reassurances (“Don’t worry, it will all work out fine”). Such responses may offer temporary comfort, but they won’t help you or him explore the larger issues involved.

Instead, you can help him express his fears by using “reflective listening,” a technique Elizabeth Dugan recommends when talking about driving and other difficult issues with an elderly parent or other older adult. Reflective listening — which essentially means rephrasing what the person has said — conveys support and encouragement and helps the speaker gain insight about his experience.

To use reflective listening in the example above, you could say something like, “Look, I know you’re probably worried that giving up driving would mean you have to give up some of your usual activities.” This type of response will encourage him to keep talking about his worries and reflect upon them, which is an important step in working through major problems and transitions.

Allow Space for a Long Conversation

When reflecting about driving and its role in your aging loved one’s life, don’t be surprised if they begin to talk about the past. He or she may reminisce about his honeymoon road trip to the Grand Canyon or recall how he saved up money for their first car or taught all the kids how to drive.

Resist the temptation to interrupt and get them back on track. Instead, try to encourage the reminiscences by asking questions or even requesting to see photos. Sifting through memories will help them come to terms with this life transition as they reflect on the role driving has played in their life and gradually accept the fact that they’ll soon have to give it up.

As the discussion progresses, ask your loved one directly what he or she thinks they should do about driving. You may want to help them jot down some of the pros and cons of the alternatives they face. This approach can help someone realize that there are actually some benefits to not driving (tremendous savings on auto insurance, car maintenance, and gasoline, for example). It also may help focus them on the stark consequences — such as a fatal accident — that could result from maintaining the status quo.

Depending on how everyone is feeling, this might be a good point to put the discussion on temporary hold. Agree to meet again in a couple of days, after you’ve all had a chance to reflect on the various options. (You might want to set a specific time to meet to ensure that it happens.)

Of course, there’s no telling how the discussion will unfold, since that will have a lot to do with factors unique to the situation. But the discussion is much more likely to be productive and positive if you approach it with a genuine desire to learn more about his experiences, ideas, and concerns.

Find Out if Other Issues Are Affecting Driving

Find out if medical problems are causing driving issues. If the person you’re caring for acknowledges that they’re having difficulty driving, find out the specific problems. Make appointments with their physician and eye doctor, and be sure to ask about medication, side effects and drug interactions. It’s possible that the problem can be remedied with a change in medication or a stronger pair of glasses. Make sure that your loved one’s car is suited to their needs and physical abilities, and ask their doctor if assistive devices might help address driving difficulties.

Discuss interim measures, if possible. Once you determine the source of the problem, you can decide what to do next. Your loved one’s doctor might suggest limiting driving to daylight hours or essential errands. If they’re going to continue to drive at all, it’s a good idea for them to brush up on their driving skills and the traffic laws by taking a senior driving refresher course. Organizations such as AARP, AAA and commercial driving schools all offer these types of courses. Agree to revisit the decision every few months to see how it’s going.

Help explore other transportation options. Whether or not your elderly loved one has to give up the car keys immediately, it’s a good idea to help them become familiar with other transportation options. Take the bus with him or her if they’re apprehensive and help them find out more about local senior transportation services. Encourage them to carpool with friends.

Take a break if they refuse to address the issue of driving safety. Your loved one may become angry when you try to talk about driving or refuse to discuss it, so it’s a good idea to temporarily drop the issue. There’s no point in engaging in a battle — it will only make them more resistant. Give the matter some time, and then bring it up again in a week or so. You may find that they’ve become more receptive to discussing the matter over time, as they grow used to the idea and realize that the risks of continuing to drive outweigh the benefits.

How can I persuade my father to stop driving?

It depends on what’s prompting the doctor recommendations and if this was a firm, evidence-based diagnosis or an off-the-cuff, rushed remark.

If there’s any doubt, get a multidisciplinary assessment of his driving fitness. The American Occupational Therapy Association has a database listing certified driving rehabilitation specialists so you can find one in your area (http://www1.aota.org/driver_search/index.aspx). It may be that with retraining or some adaptation your father can keep driving safely or modify his driving behavior to minimize risks.

However if he can’t, then it’s time to intervene. Start by talking. Ask open-ended questions to find out how he sees the issue. On average we’ll outlive our ability to drive by about ten years. Has he thought about how he will get around when he is no longer safe to drive? What are the alternatives to driving that he is comfortable with? If talking calmly and openly doesn’t work you may have to try other steps.

Medically unfit drivers can be reported to the licensing authority (i.e., department of motor vehicles). State’s differ in how they respond to reports, but it usually triggers official action that may compel him to make the change.

Ways to Help a Senior Transition From Driving

Giving up driving won’t be easy for the person in your care, both from a practical standpoint and an emotional one. No more driving can result in increased isolation and dependency. In some cases, it means that an older adult can no longer live on their own.

You can help support your loved one emotionally through this transition in several important ways:

- Listen. You may feel like changing the subject when he or she speaks wistfully about driving or their car, but resist the impulse, especially during the first few weeks after they stop driving. Your loved one is mourning a major loss, and talking about it will help them come to terms with their grief. Don’t attempt to jolly them out of their sad mood or find the silver lining in the situation. Instead, just listen.

- Share memories. Encourage your loved one to talk about some of their cherished driving memories, look at photos together and ask about their favorite driving experiences. Revisiting the role driving has played is their life will help them get through the grieving process.

- Watch for signs of depression. If he or she shows signs of melancholy or seems withdrawn or particularly irritable, these could be symptoms of depression. Other symptoms can include sleeplessness, fatigue, and loss of appetite or excessive eating. If you suspect that your loved one is depressed, consult their doctor.

- Be there. Make a point of being even more available than usual to your loved one during this transition period. Check in regularly and be sure to include them in family activities. Encourage them to keep up social contacts and offer to drive them when you can. If you live far away, check in frequently by phone and visit as often as possible.

Practical Steps to Help a Senior Stop Driving

Along with supporting an older loved one emotionally when they have to give up driving, you can also find practical ways to help them make the transition to being car-less.

- Learn about paratransit. Research local paratransit and other alternative transportation options, and accompany him the first few times he tries public transportation to make him feel more comfortable with it.

- Identify informal transportation options. Brainstorm possible transportation opportunities. Is there a neighbor or friend who would be willing to drive your loved one for a small fee or even no fee? Options that incorporate opportunities for social contacts are especially helpful, such as carpooling with other older adults to activities at the local senior center.

- Help him or her find activities that don’t involve driving. Your loved one may need help, especially at first, finding ways to occupy their time without a car. Suggest possible volunteer activities and other projects. Is there a school nearby that needs tutors, for example, or a hospital where they could read to sick children? Offer to help if he or she wants to launch a house project, like organizing their garage or planting a garden. Make sure they’re aware of local activities and resources for older adults in their area.

- Do some additional research to find information for your loved one. AAA offers advice for caregivers, as well as information about transportation resources around the country. The National Association of Area Agencies on Aging also provides its own guide: Transportation Options for Older Adults. The American Public Transportation Association offers a directory of mass transportation resources around the country.

Wherever older adults are on the driving continuum — whether they’re still driving, driving with restrictions, or must give up driving altogether — you can play a valuable role. Your caring, active participation in their lives will reassure them that ceasing to drive doesn’t have to sentence them to isolation and boredom. Below are some steps you can take to help them transition to life after driving.

- Make it a habit to check in on them often, just to chat or share some news.

- Offer to drive them to the activities they enjoy — or help find someone else who can take them.

- See that they’re included in family outings, like their grandchildren’s school events or a day at the beach.

- Encourage them to try taking the bus on their next trip to the pharmacy, or to walk, if it isn’t too far away, and offer to go with them if you can.

- Urge them to ask for rides from friends, and to reciprocate in whatever way they can (preparing a meal, for example).

- Help them develop new routines and interests that don’t require driving, like gardening, walking, or swimming at the local pool.

- Your support and involvement in their lives will make giving up the car a far less lonely and frightening prospect.

Transportation Options for Seniors Who No Longer Drive

If your elderly loved one is no longer able to drive, chances are that he or she also needs the following forms of assistance:

- Help from family caregivers, friends or neighbors

- Help from paid caregivers

- Transportation as included in a long-term care community or adult day care center

For those not receiving these forms of assistance or care, there are other ways to get around, including:

- Local public transportation or subsidized transportation options designed specifically for elderly or disabled riders

- Ride-sharing options such as those highlighted below

Top Ridesharing Options for Seniors

Transportation is rapidly changing, not least because of the proliferation of new ride-hailing services such as Uber and Lyft. In a short time, these convenient services have become crucial for getting around cities.

You might think these kinds of services have been a boon for seniors who are unable to drive. But many seniors either don’t have a smartphone or aren’t comfortable using it. Others may need cars with handicap accessibility or help getting to and from the door. Furthermore, ride-hailing services are really only available in cities, leaving people who live in more rural areas without these options.

Luckily, a variety of services have cropped up recently to help seniors, and their caregivers, address some of these challenges, including recent initiatives by industry leaders Uber and Lyft.